Hardware Description Languages

- Hardware Description Languages

- Introduction

- Combinational Logic

- Structural Modeling

- Sequential Logic

- More Combinational Logic

- Finite State Machines

Hardware Description Languages

Introduction

Thus far we have focused on designing combinational and sequential digital circuits at the schematic level. The process of finding an efficient set of logic gates to perform a given function is labor intensive and error prone, requiring manual simplification of truth tables or Boolean equations and manual translation of finite state machines (FSMs) into gates. In the 1990’s, designers discovered that they were far more productive if they worked at a higher level of abstraction, specifying just the logical function and allowing a computer-aided design (CAD) tool to produce the optimized gates. The specifications are generally given in a hardware description language (HDL). The two leading hardware description languages are Verilog and VHDL. We will focus on Verilog only.

Modules

A block of hardware with inputs and outputs is called a module. An gate, a multiplexer, and a priority circuit are all examples of hardware modules. The two general styles for describing module functionality are behavioral and structural. Behavioral models describe what a module does. Structural models describe how a module is built from simpler pieces; it is an application of hierarchy. The Verilog code in the example illustrates behavioral descriptions of a module that computes the Boolean function . The module is named sillyfunction and has three inputs a, b and c, and one output, y.

A Verilog module begins with the module name and a listing of the inputs and outputs. The assign statement describes combinational logic. ~ indicates , & indicates and | indicates .

Verilog signals such as the inputs and outputs are Boolean variables. They may also have floating and undefined values.

module sillyfunction (input a, b, c,

output y);

assign y = ~a & ~b & ~c |

a & ~b & ~c |

a & ~b & c;

endmodule

A module is a good application of modularity. It has a well defined interface, consisting of its inputs and outputs, and it performs a specific function. The particular way in which it is coded is unimportant to others that might use the module,by as long as it performs its function.

Language Origins

Verilog was developed by Gateway Design Automation as a proprietary language for logic simulation in 1984. Gateway was acquired by Cadence in 1989 and Verilog was made an open standard in 1990 under the control of Open Verilog International. The language became an IEEE standard in 1995 (IEEE STD 1364) and was updated in 2001.

Simulation and Synthesis

The two major purposes of HDLs are logic simulation and synthesis. During simulation, inputs are applied to a module, and the outputs are checked to verify that the module operates correctly. During synthesis, the textual description of a module is transformed into logic gates.

Simulation

Humans routinely make mistakes. Such errors in hardware design are called bugs. Eliminating bugs from a digital system is obviously important, especially when customers are paying money and lives depend on the correct operation. Testing a system in the laboratory is time-consuming. Discovering the cause of errors in the lab can be extremely difficult, because only signals routed to the chip pins can be observed. There is no way to directly observe what is happening inside a chip. Correcting errors after the system is built can be devastatingly expensive. For example, correcting a mistake in cutting-edge integrated circuits costs more than a million dollars and takes several months. Intel’s famous FDIV (floating point division) bug in the Pentium processor forced the company to recall chips after they had shipped, at a total cost of 475 million dollars. Logic simulation is essential to test a system before it is built.

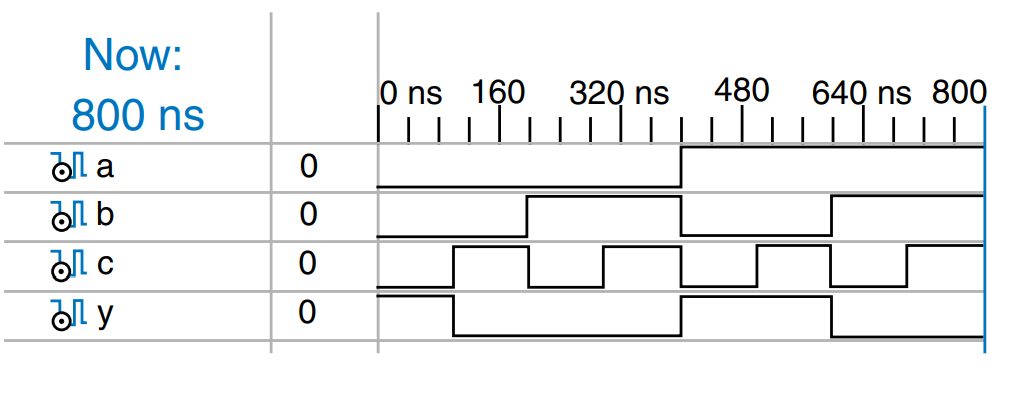

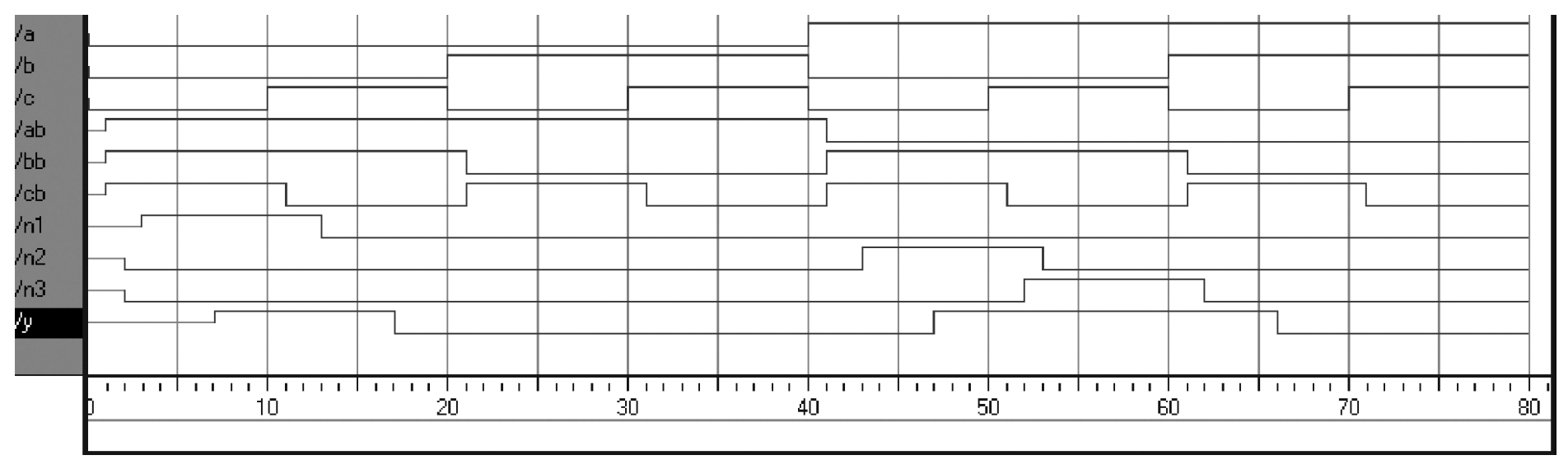

The figure shows waveforms from a simulation of the previous sillyfunction module demonstrating that the module works correctly. y is TRUE when a, b and c are 000, 100, or 101, as specified by the Boolean equation.

Synthesis

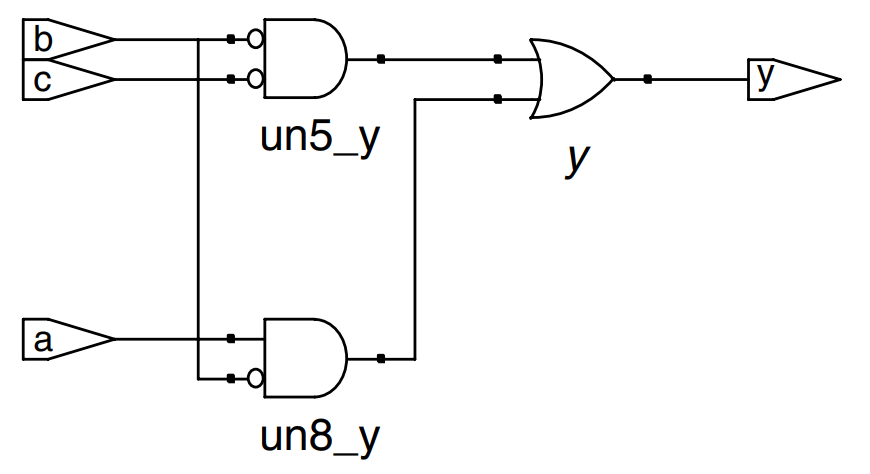

Logic synthesis transforms HDL code into a netlist describing the hardware (e.g., the logic gates and the wires connecting them). The logic synthesizer might perform optimizations to reduce the amount of hardware required. The netlist may be a text file, or it may be drawn as a schematic to help visualize the circuit. The figure shows the results of synthesizing the sillyfunction module. Notice how the three three-input gates are simplified into two two-input gates using Boolean algebra.

CIrcuit descriptions in HDL resemble code in a programming language. However, one must remember that the code is intended to represent hardware. Verilog is a rich language with many commands. Not all of these commands can be synthesized into hardware. For example, a command to print results on the screen during simulation does not translate into hardware. Because our primary interest is to build hardware, we will emphasize a synthesizable subset of the language. Specifically, we will divide HDL code into synthesizable modules and a testbench. The synthesizable modules describe the hardware. The testbench contains code to apply inputs to a module, check whether the output results are correct, and print discrepancies between expected and actual outputs. Testbench code is intended only for simulation and cannot be synthesized.

HDLs have specific ways of describing various classes of logic; these ways are called idioms.

Combinational Logic

Bitwise Operators

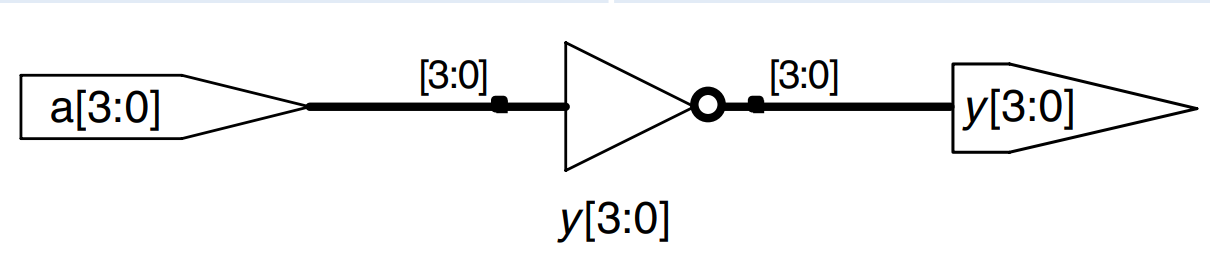

Bitwise operators act on single-bit signals or on multi-bit busses. For example, the inv module shown describes four inverters connected to 4-bit busses.

a[3:0] represents a 4-bit bus. The bits, from most significant to least significant, are a[3], a[2], a[1], a[0]. This is called little-endian order because the least significant byte has the smallest bit number.

We could also have used a[0:3], in which case the bits, from most significant to least significant, would be a[0], a[1], a[2] and a[3]. This is called big-endian order.

The endianness of a bus is purely arbitrary. Indeed, endianness is also irrelevant to this example, because a bank of inverters doesn’t care what the order of the bits are. Endianness matters only for operators, such as addition, where the sum of one column carries over into the next. Either ordering is acceptable, as long as it is used consistently. We will consistently use the little-endian order, [N-1:0] in Verilog for an -bit bus.

module inv (input [3:0] a,

output [3:0] y);

assign y = ~a;

endmodule

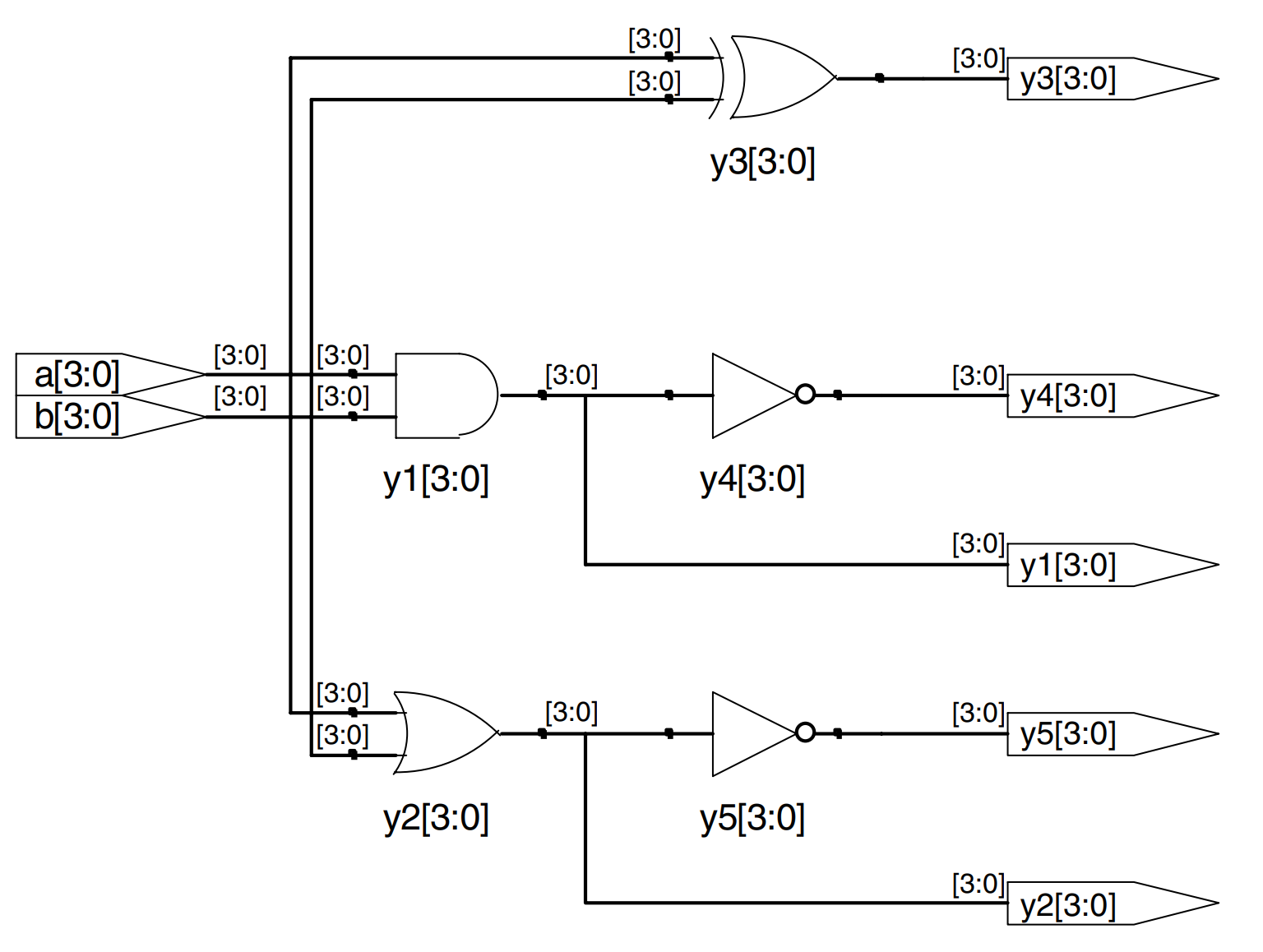

The gates module in this example demonstrates bitwise operations acting on 4-bit busses for other basic logic functions.

~, ^, and | are examples of Verilog operators, whereas a, b, and y1 are operands. A combination of operators and operands, such as a & b, or ~(a | b), is called an expression. A complete command such as assign y4 = ~(a & b); is called a statement.

assign out = in1 op in2; is called a continuous assignment statement. Continuous assignment statements end with a semicolon. Anytime the inputs on the right side of the = in a continuous assignment statement change, the output on the left side is recomputed. Thus, continuous assignment statements describe combinational logic.

module gates (input [3:0] a, b,

output [3:0] y1, y2,

y3, y4, y5);

assign y1 = a & b; // AND

assign y2 = a | b; // OR

assign y3 = a ^ b; // XOR

assign y4 = ~(a & b); // NAND

assign y5 = ~(a | b); // NOR

endmodule

Comments and White Space

The gates example showed how to format comments. Verilog is not picky about the use of white space. Nevertheless, proper indenting and use of blank lines is helpful to make nontrivial designs readable. Be consistent in your use of capitalization and underscores in signal and module names. Module and signal names must not begin with a digit.

Verilog comments are just like those in C or Java. Comments beginning with /* continue, possibly across multiple lines, to the next */. Comments beginning with // continue to the end of the line.

Verilog is case-sensitive. y1 and Y1 are different signals in Verilog.

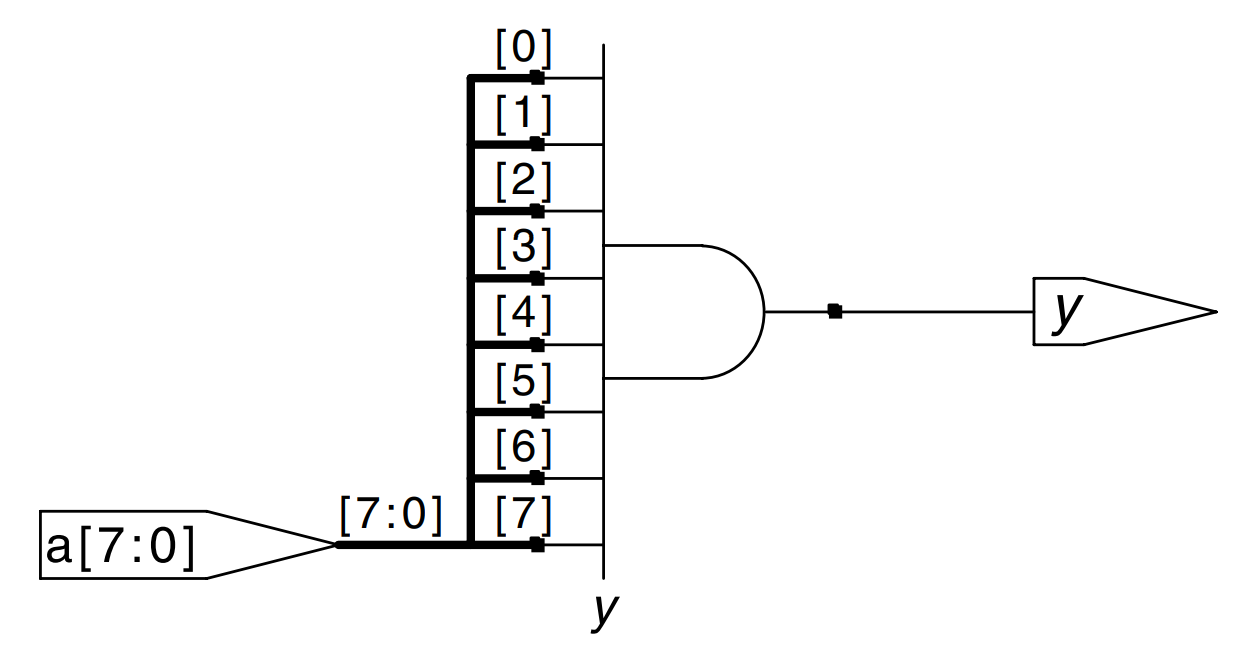

Reduction Operators

Reduction operators imply a multiple-input gate acting on a single bus. The example describes an eight-input gate with inputs a_7, a_6,...,a_0.

As one would expect, |, ^, ~&, and ~| reduction operators are available for , , , and as well. Recall that a multi-input performs parity, returning TRUE if an odd number of inputs are TRUE.

module and8 (input [7:0] a,

output y);

assign y = &a;

// &a is much easier to write than

// assign y = a[7] & a[6] & a[5] & a[4] &

// a[3] & a[2] & a[1] & a[0];

endmodule

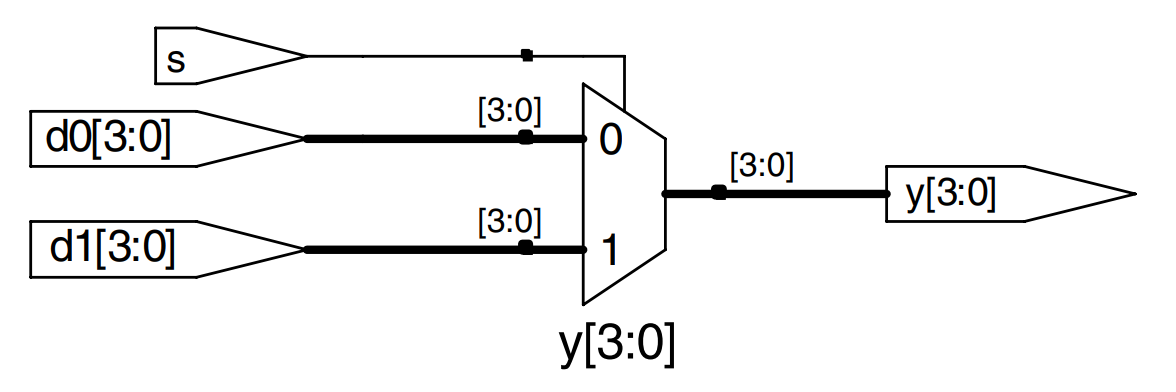

Conditional Assignment

Conditional assignments select the output from among alternatives based on an input called the condition. The example illustrates a 2:1 multiplexer using conditional assignment.

The conditional operator ?: chooses, based on a first expression, between a second and third expression. The first expression is called the condition. If the condition is 1, the operator chooses the second expression. If the condition is 0, the operator chooses the third expression.

?: is especially useful for describing a multiplexer because, based on the first input, it selects between two others. The example code demonstrates the idiom for a 2:1 multiplexer with 4-bit inputs and outputs using the conditional operator.

module mux2 (input [3:0] d0, d1,

input s,

output [3:0] y);

assign y = s ? d1 : d0;

endmodule

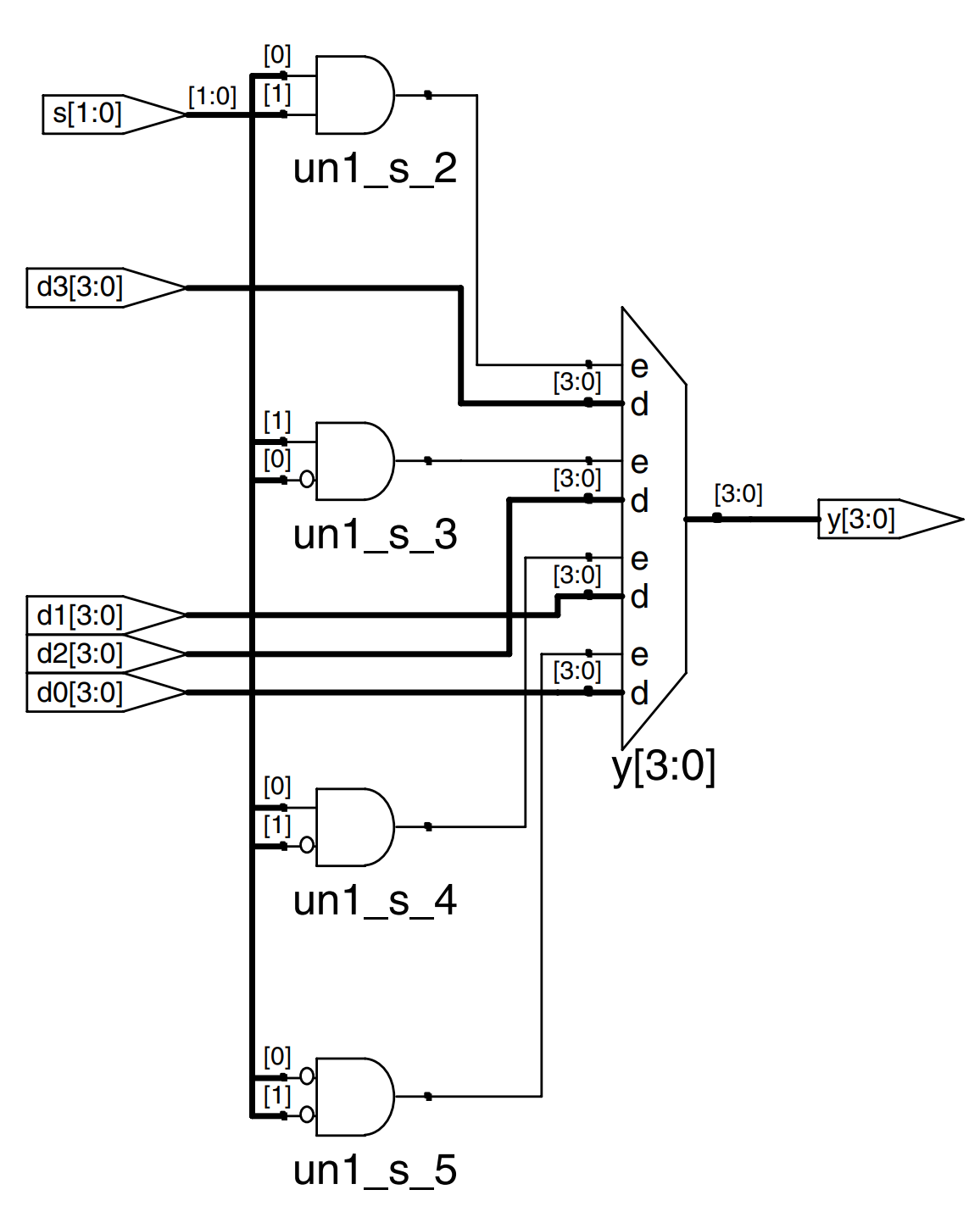

This example shows a 4:1 multiplexer based on the same principle as the 2:1 multiplexer in the previous example.

The synthesized circuit’s multiplexer in the schematic has multiple data and one-hot enable inputs. When one of the enables is asserted, the associated data is passed to the output.

if s[1] is 1, then the multiplexer chooses the first expression, (s[0] ? d3 : d2). This expression in turn chooses either d3 or d2 based on s[0] (y = d3 if s[0] is 1 and d2 if s[0] is 0). If s[1] is 0, then the multiplexer similarly chooses the second expression, which gives either d1 or d0 based on s[0].

module mux4 (input [3:0] d0, d1, d2, d3,

input [1:0] s,

output [3:0] y);

assign y = s[1] ? (s[0] ? d3 : d2)

: (s[0] ? d1 : d0);

endmodule

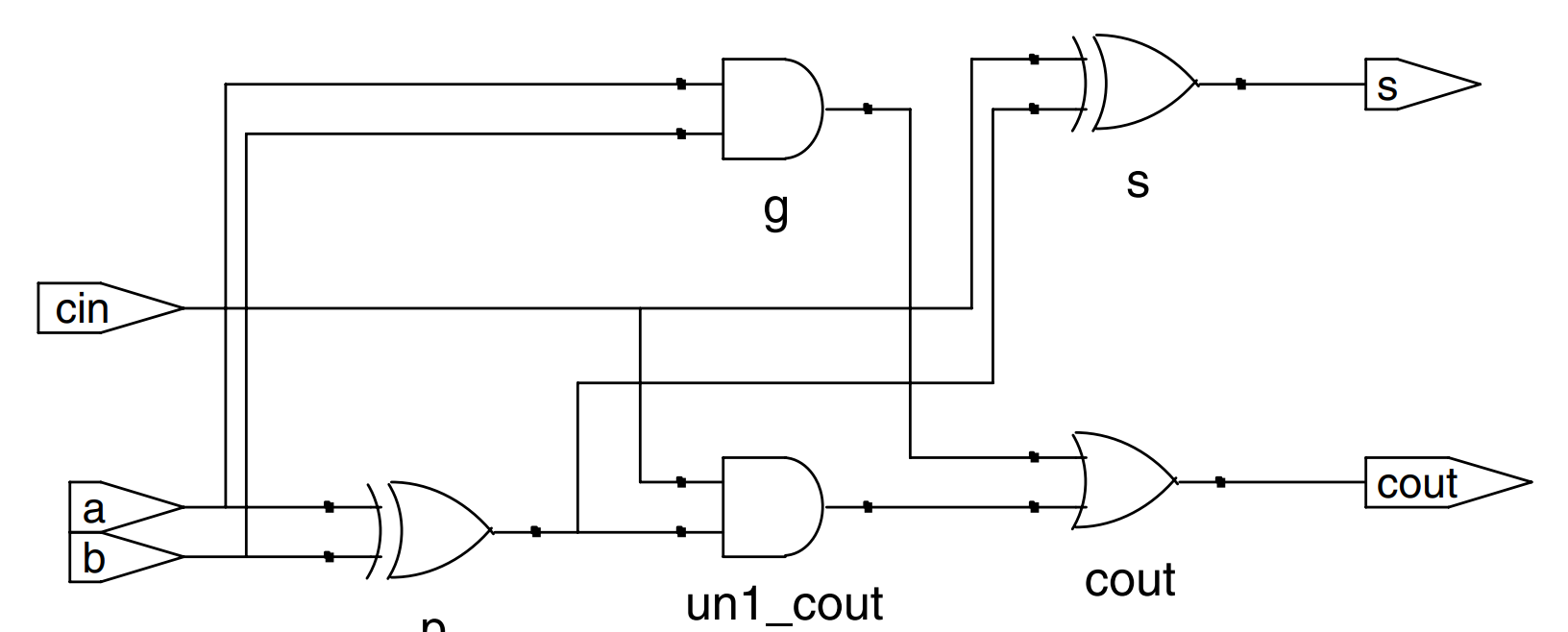

Internal Variables

Often it is convenient to break a complex function into intermediate steps.

A full adder for example is a circuit with three inputs and two outputs defined by the following equations:

If we define intermediate signals, and ,

we can rewrite the full adder as follows:

and are called internal variables, because they are neither inputs nor outputs but are used only internal to the module. The example shows how they are used in HDLs.

HDL assignment statements take place concurrently. In an HDL, the order does not matter. Like hardware, HDL assignment statements are evaluated any time the inputs, signals on the right hand side, change their value, regardless of the order in which the assignment statements appear in a module.

In Verilog, wires are used to represent internal variables whose values are defined by assign statements such as assign p = a ^ b; Wires technically have to be declared only for multibit busses, but it is good practice to include them for all internal variables; their declaration could have been omitted in this example.

module fulladder (input a, b, cin,

output s, cout);

wire p, g;

assign p = a ^ b;

assign g = a & b;

assign s = p ^ cin;

assign cout = g | (p & cin);

endmodule

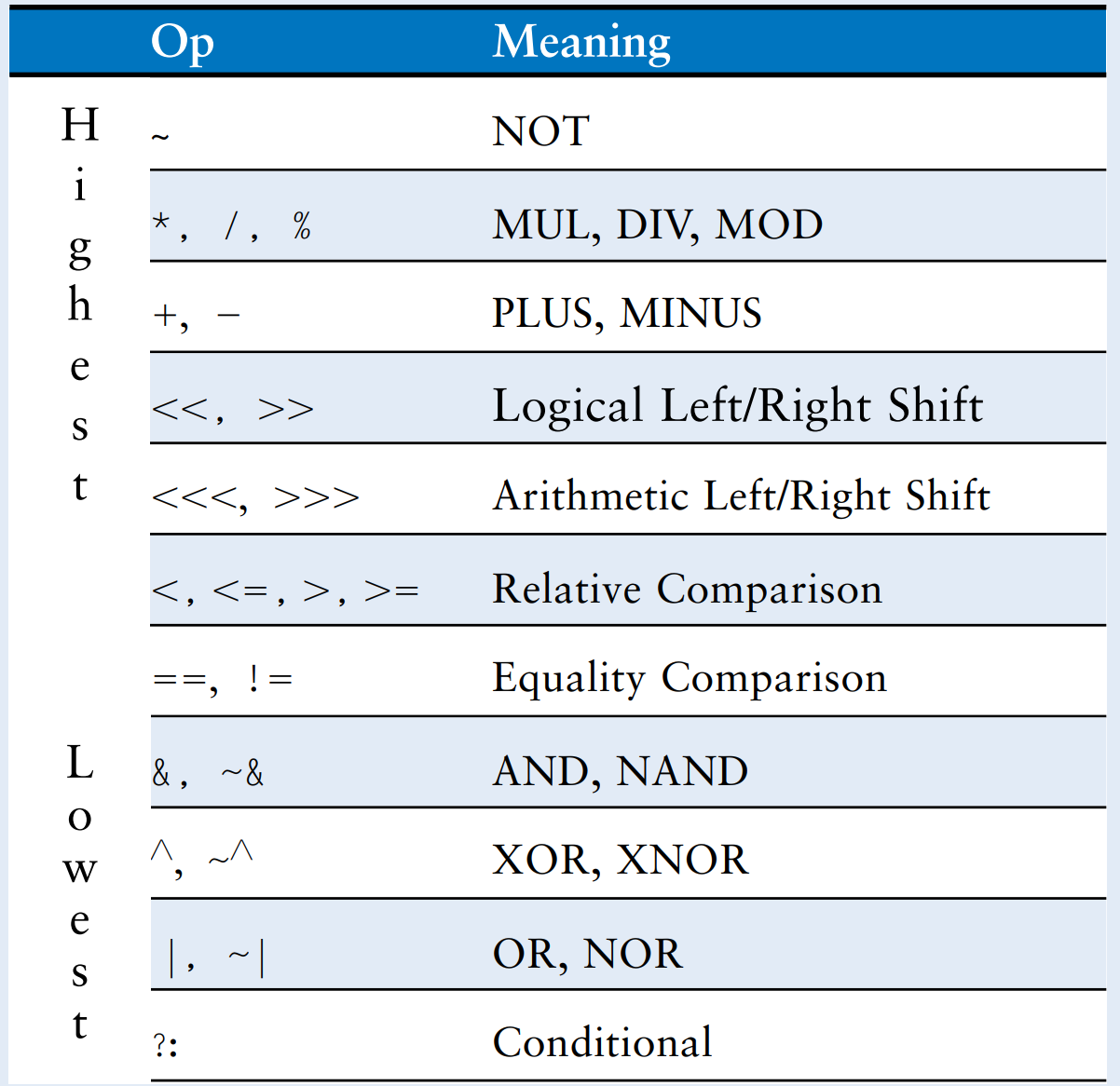

Precedence

Numbers

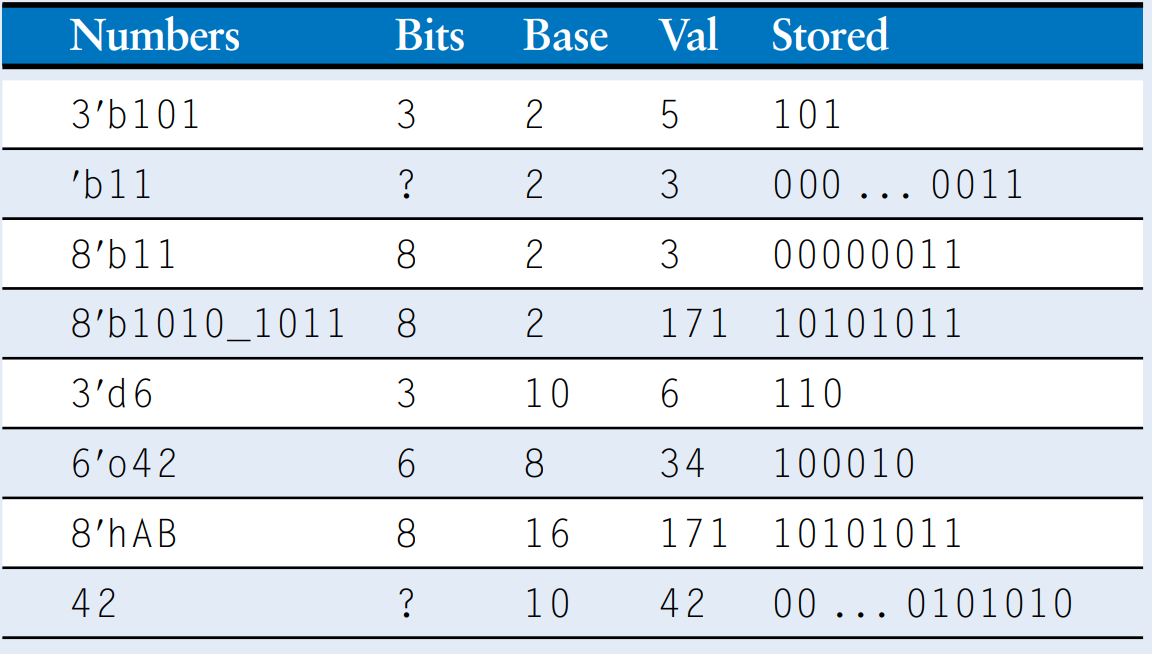

Numbers can be specified in a variety of bases. Underscores in numbers are ignored and can be helpful in breaking long numbers into more readable chunks.

Verilog numbers can specify their base and size (the number of bits used to represent them). The format for declaring constants is N'Bvalue, where N is the size in bits, B is the base, and value gives the value. For example 9'h25 indicates a 9-bit number with a value of . Verilog supports 'b for binary, 'o for octal, 'd for decimal and 'h for hexadecimal. If the base is omitted, the base defaults to decimal.

If the size is not given, the number is assumed to have as many bits as the expression in which it is being used. Zeros are automatically padded on the front of the number to bring it up to full size. For example, if w is a 6-bit bus, assign w = 'b11 gives w the value 000011. It is better practice to explicitly give the size.

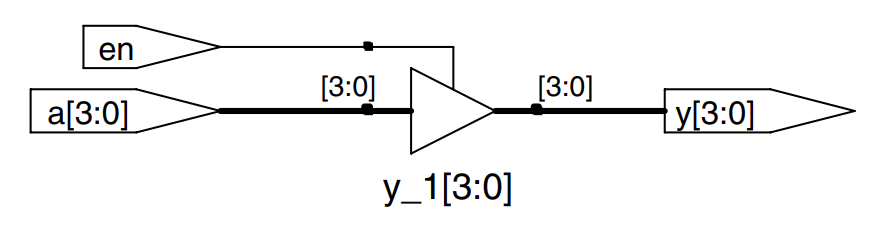

Z’s and X’s

HDLs use z to indicate a floating value. z is particularly useful for describing a tristate buffer, whose output floats when the enable is 0. The example shows the idiom for a tristate buffer. If the buffer is enabled, the output is the same as the input. If the buffer is disabled, the output is assigned a floating value.

module tristate (input [3:0] a,

input en,

output [3:0] y),

assign y = en ? a : 4'bz;

endmodule

Similarly, HDLs use x to indicate an invalid logic level. If a bus is simultaneously driven to 0 and 1 by two enabled tristate buffers (or other gates), the result is x, indicating contention. If all the tristate buffers driving a bus are simultaneously OFF, the bus will float, indicated by z.

At the start of simulation, state nodes such as flip-flop outputs are initialized to an unknown state. This is helpful to track errors caused by forgetting to reset a flip-flop before its output is used.

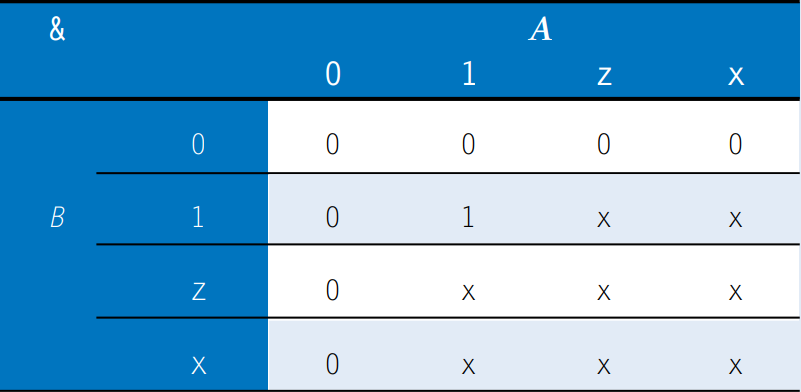

If a gate receives a floating input, it may produce an x output when it can’t determine the correct output value. Similarly, if it receives an illegal or uninitialized input, it may produce an x output. The example shows how Verilog combines these different signal values in logic gates.

Verilog signal values are 0, 1, z and x. Verilog constants starting with z or x are padded with leading z’s or x’s (instead of 0’s) to reach their full length when necessary.

The table shows a truth table for an gate using all four possible signal values. Note that the gate can sometimes determine the output despite some inputs being unknown. For example 0 & z returns 0 because the output of an gate is always 0 if either input is 0. Otherwise, floating or invalid inputs cause invalid outputs.

Seeing x values in a simulation is almost always an indication of a bug or bad coding practice. In the synthesized circuit, this corresponds to a floating gate input, uninitialized state, or contention. The x may be interpreted randomly by the circuit as 0 or 1, leading to unpredictable behavior.

Bit Swizzling

Often it is necessary to operate on a subset of a bus or to concatenate (join together) signals to form busses. These operations are collectively known as bit swizzling. In the example, y is given the 9-bit value using bit swizzling operations.

The {} operator is used to concatenate busses. {3{d[0]}} indicates three copies of d[0].

don’t confuse the 3-bit binary constant 3'b101 with a bus named b. Note that it was critical to specify the length of 3 bits in the constant; otherwise, it would have had an unknown number of leading zeros that might appear in the middle of y.

if y were wider than 9 bits, zeros would be placed in the most significant bits.

assign y = {c[2:1], {3{d[0]}}, c[0], 3'b101};

Delays

HDL statements may be associated with delays specified in arbitrary units. They are helpful during simulation to predict how fast a circuit will work (if one specify meaningful delays) and also for debugging purposes to understand cause and effect (deducing the source of a bad output is tricky if all signals change simultaneously in the simulation results). These delays are ignored during synthesis; the delay of a gate produced by the synthesizer depends on its and specifications, not on numbers in HDL code.

The example adds delays to the original function from the first example, . It assumes that inverters have a delay of 1 ns, three-input gates have a delay of 2 ns, and three-input gates have a delay of 4 ns. The figure shows the simulation waveforms, with y lagging 7 ns after the inputs. Note that y is initially unknown at the beginning of a simulation.

Verilog files can include a timescale directive that indicates the value of each time unit. The statement is of the form 'timescale unit/precision. In this file, each unit is 1 ns, and the simulation has 1 ps precision. If no timescale directive is given in the file, a default unit and precision (usually 1 ns for both) is used. In Verilog, a # symbol is used to indicate the number of units of delay. It can be placed in assign statements, as well as non-blocking (<=) and blocking (=) assignments, which will be discussed.

‘timescale 1ns/1ps

module example (input a, b, c,

output y);

wire ab, bb, cb, n1, n2, n3;

assign #1 {ab, bb, cb} = ~{a, b, c};

assign #2 n1 = ab & bb & cb;

assign #2 n2 = a & bb & cb;

assign #2 n3 = a & bb & c;

assign #4 y = n1 | n2 | n3;

endmodule

Structural Modeling

The previous section discussed behavioral modeling, describing a module in terms of the relationships between inputs and outputs. This section examines structural modeling, describing a module in terms of how it is composed of simple modules.

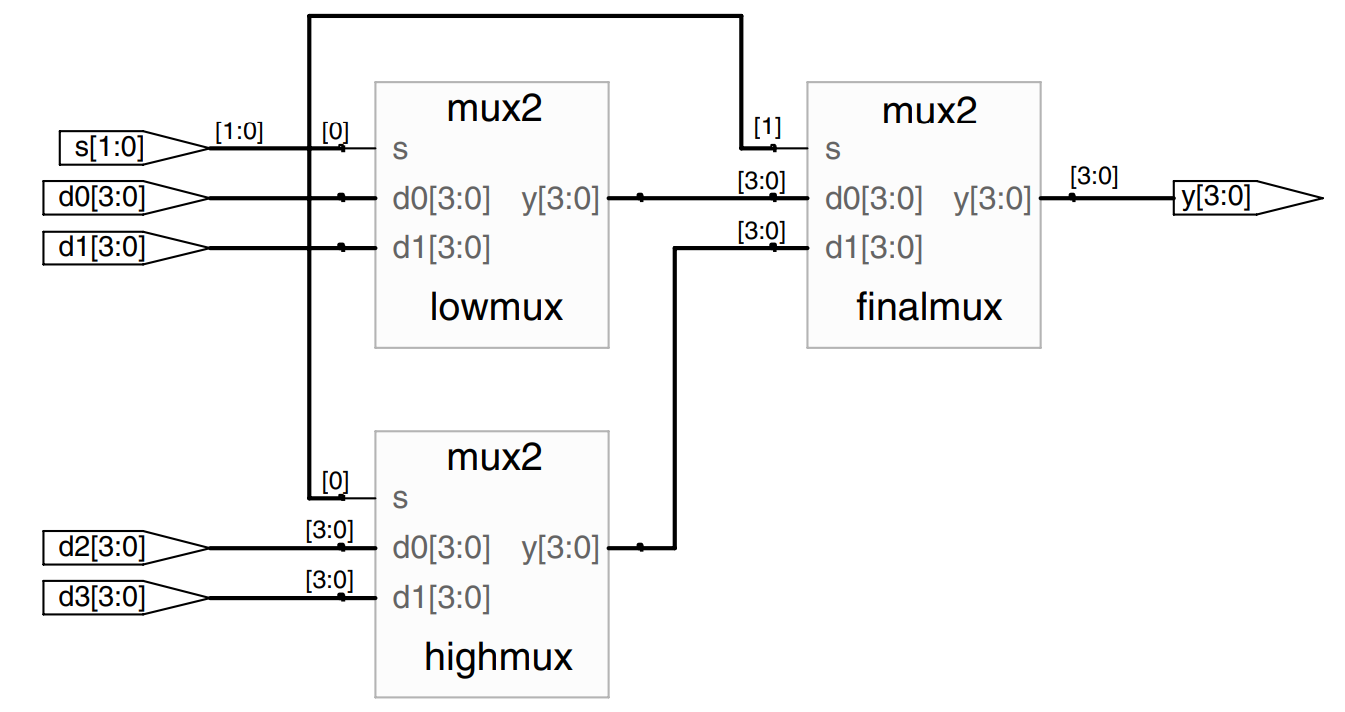

This example shows how to assemble a 4.1 multiplexer from three 2:1 multiplexers. Each copy of the 2:1 multiplexer is called an instance. Multiple instances of the same module are distinguished by distinct names, in this case lowmux, highmux and finalmux. This is an example of regularity, in which the 2:1 multiplexer is reused many times.

The mux2 module must be defined elsewhere in the Verilog source.

module mux4 (input [3:0] d0, d1, d2, d3,

input [1:0] s,

output [3:0] y);

wire [3:0] low, high,

mux2 lowmux (d0, d1, s[0], low);

mux2 highmux (d2, d3, s[0], high);

mux2 finalmux (low, high, s[1], y);

endmodule

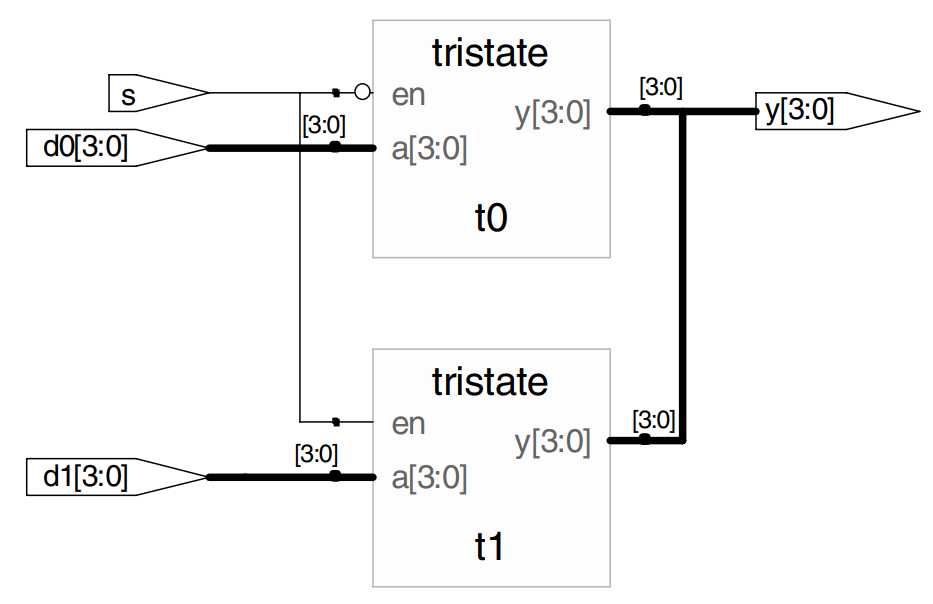

This example uses structural modeling to construct a 2:1 multiplexer from a pair of tristate buffers.

In Verilog, expressions such as ~s are permitted in the port list for an instance. Arbitrarily complicated expressions are legal but discouraged because they make the code difficult to read.

module mux2 (input [3.0] d0, d1,

input s,

output [3:0] y);

tristate t0 (d0, ~s, y);

tristate t1 (d1, s, y);

endmodule

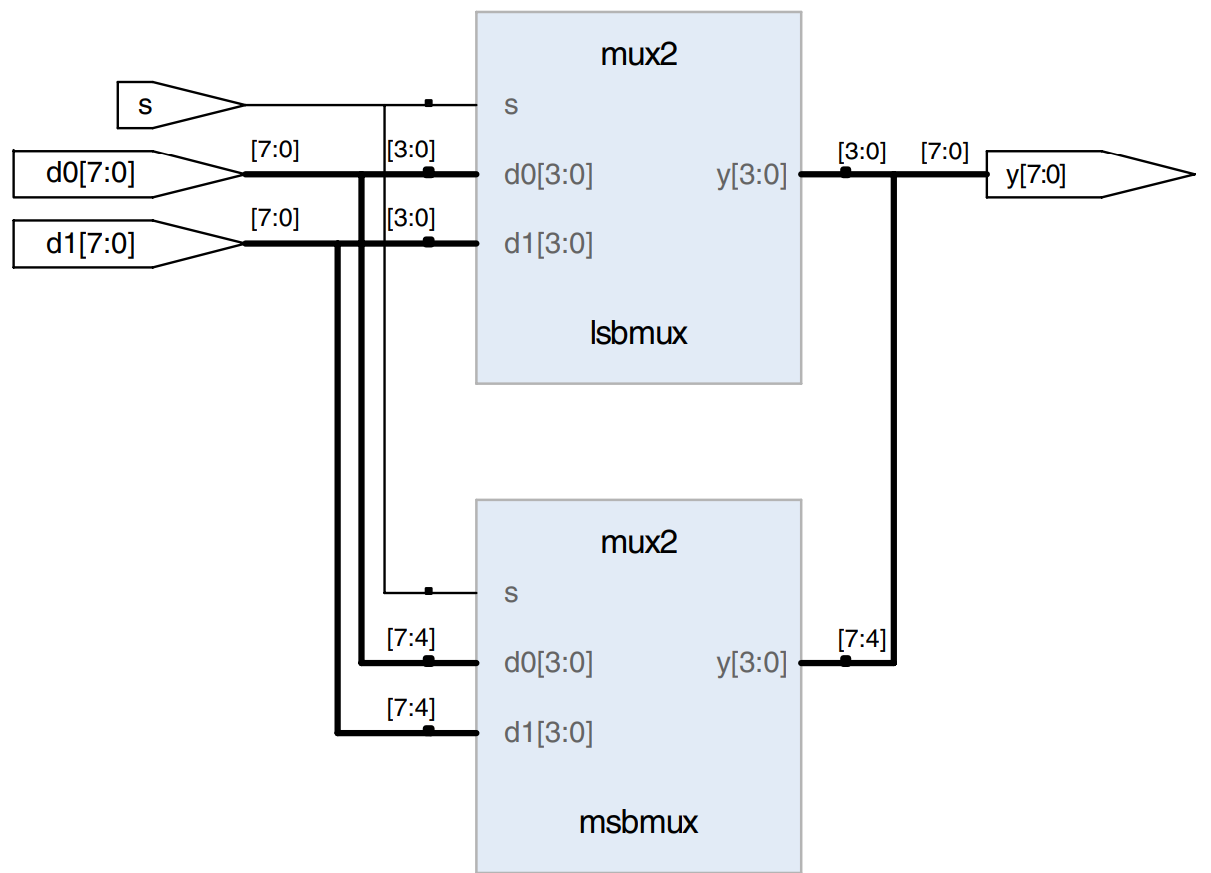

This example shows how modules can access part of a bus. An 8-bit wide 2:1 multiplexer is built using two of the 4-bit 2:1 multiplexers already defined, operating on the low and high nibbles of the byte.

module mux2_8 (input [7:0] d0, d1,

input s,

output [7:0] y);

mux2 lsbmux (d0[3:0], d1[3:0], s, y[3:0]);

mux2 msbmux (d0[7:4], d1[7:4], s, y[7:4]);

endmodule

In general, complex systems are designed hierarchically. The overall system is described structurally by instantiating its major components. Each of these components is described structurally from its building blocks, and so forth recursively until the pieces are simple enough to describe behaviorally. It is good style to avoud (or at least to minimize) mixing structural and behavioral descriptions within a single module.

Sequential Logic

Registers

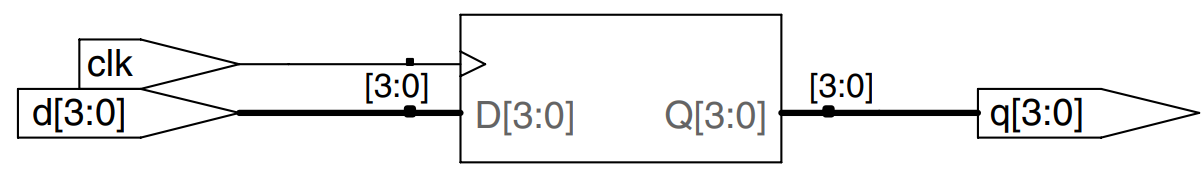

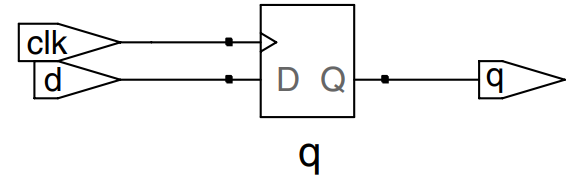

The vast majority of modern commercial systems are built with registers using positive edge-triggered D flip-flops. The example shows the idiom for such flip-flops.

In Verilog always statements, signals keep their old value until an event in the sensitivity list takes place that explicitly causes them to change. Hence, such code, with appropriate sensitivity lists, can be used to describe sequential circuits with memory. For example, the flip-flop includes only clk in the sensitivity list. It remembers its old value of q until the next rising edge of the clk, even if d changes in the interim.

In contrast, Verilog continuous assignment statements (assign) are reevaluated anytime any of the inputs on the right hand side changes. Therefore, such code necessarily describes combinational logic.

A Verilog always statement is written in the form

always @ (sensitivity list)

statement;

The statement is executed only when the event specified in the sensitivity list occurs. In this example, the statement is q <= d. Hence, the flip-flop copies d to q on the positive edge of the clock and otherwise remembers the old state of q.

<= is called a nonblocking assignment. Think of it as a regular = for the moment, we’ll discuss the details later. Note that <= is used instead of assign inside an always statement.

All signals on the left hand side of <= or = in an always statement must be declared as reg. In this example, q is both an output and a reg, so it is declared as output reg [3:0] q. Declaring a signal as reg does not mean the signal is actually the output of a register. All it means is that the signal appears on the left hand side of an assignment in an always statement.

module flop (input clk,

input [3:0] d,

output reg [3:0] q);

always @ (posedge clk)

q <= d;

endmodule

Resettable Registers

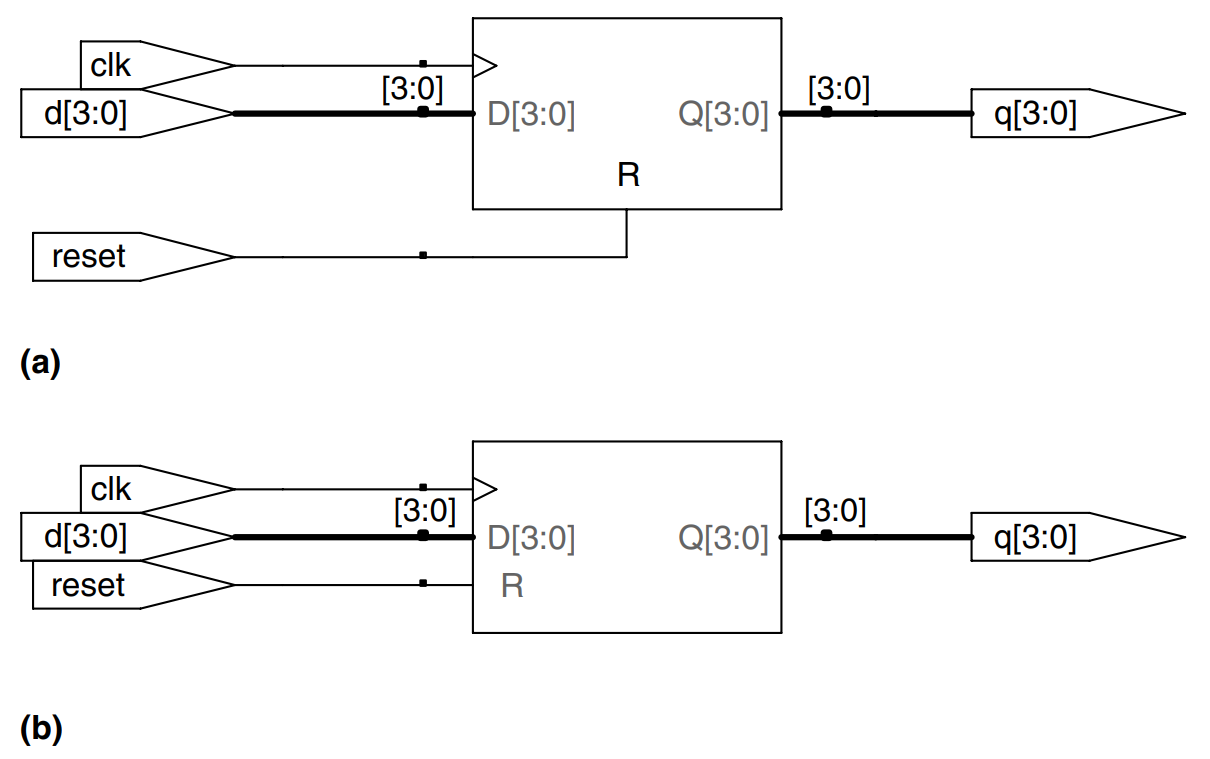

When simulation begins or power is first applied to a circuit, the output of a flop or register is unknown. This is indicated with x in Verilog. Generally, it is good practice to use resettable registers so that on powerup one can put the system into a known state. The reset may be either asynchronous or synchronous. Recall that asynchronous reset occurs immediately, whereas synchronous reset clears the output only on the next rising edge of the clock. The example demonstrates the idioms for flip-flops with asynchronous and synchronous resets. Note that distinguishing synchronous and asynchronous reset in a schematic can be difficult. Our schematics place asynchronous reset at the bottom of a flip-flop and synchronous reset on the left side.

Multiple signals in an always statement sensitivity list are separated with a comma or the word or. Notice that posedge reset is in the sensitivity list on the asynchronously resettable flop, but not on the synchronously resettable flop. Thus, the asynchronously resettable flop immediately responds to a rising edge on reset, but the synchronously resettable flop responds to reset only on the rising edge of the clock.

module flopr (input clk,

input reset,

input [3:0] d,

output reg [3:0] q);

// asynchronous reset

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) q <= 4'b0;

else q <= d:

endmodule

module flopr (input clk,

input reset,

input [3:0] d,

output reg [3:0] q);

// synchronous reset

always @ (posedge clk)

if (reset) q <= 4'b0;

else q <= d:

endmodule

Enabled Registers

Enabled registers respond to the clock only when the enable is asserted. The example shows an asynchronously resettable enabled register that retains its old value if both reset and en are FALSE.

module flopenr (input clk,

input reset,

input en,

input [3:0] d,

output reg [3:0] q);

// asynchronous reset

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) q <= 4’b0;

else if (en) q <= d;

endmodule

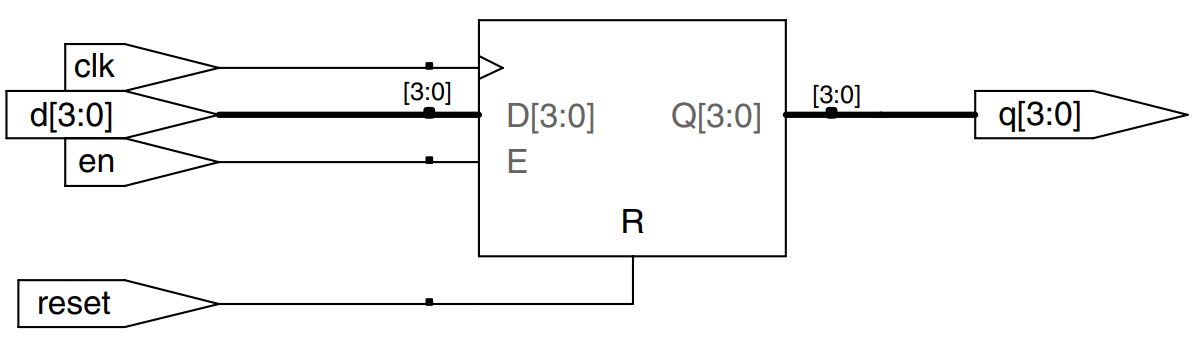

Multiple Registers

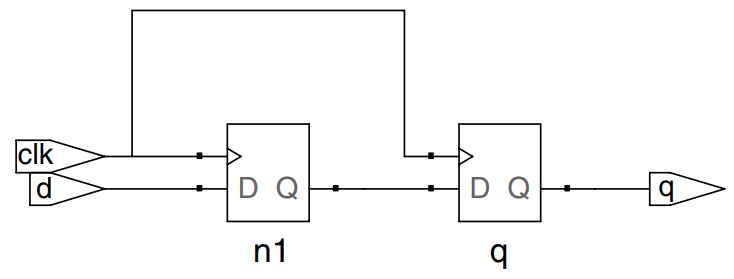

A single always statement can be used to describe multiple pieces of hardware. For example, consider our synchronizer circuit from earlier, which made use of two back-to-back flip-flops, as shown.

The example describes the synchronizer. On the rising edge of clk, d is copied to n1. At the same time, n1 is copied to q.

n1must be declared as reg because it is an internal signal used on the left hand side of <= in an always statement. Also notice that the begin/end construct is necessary because multiple statements appear in the always statement. This is analogous to { } in C or Java. The begin/end was not needed in the flopr example because if/else counts as a single statement.

module sync (input clk,

input d,

output reg q);

reg n1;

always @ (posedge clk)

begin

n1 <= d;

q <= n1;

end

endmodule

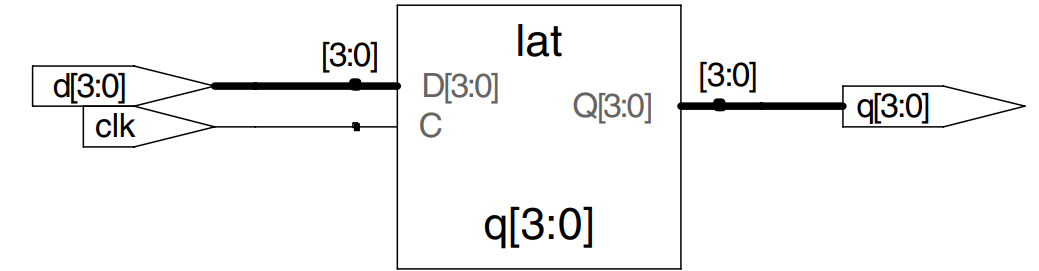

Latches

Recall from earlier that a D latch is transparent when the clock is HIGH, allowing data to flow from input to output. The latch becomes opaque when the clock is LOW, retaining its old state. The example shows the idiom for a D latch. Not all synthesis tools support latches well. Unless you know that your tool does support latches and you have a good reason to use them, avoid them and use edge-triggered flip-flops instead. Furthermore, take care that your HDL does not imply any unintended latches, something that is easy to do if you aren’t attentive. Many synthesis tools warn you when a latch is created; if you didn’t expect one, track down the bug in your HDL.

The sensitivity list contains both clk and d, so that the always statement evaluates any time clk or d changes. If clk is HIGH, d flows through to q.

q must be declared to be a reg because it appears on the left hand side of <= in an always statement. This does not always mean that q is the output of a register.

module latch (input clk,

input [3:0] d,

output reg [3:0] q);

always @ (clk, d)

if (clk) q <= d;

endmodule

More Combinational Logic

Earlier, we used assignment statements to describe combinational logic behaviorally. Verilog always statements are used to describe sequential circuits, because they remember the old state when no new state is prescribed. However, always statements can also be used to describe combinational logic behaviorally if the sensitivity list is written to respond to changes in all of the inputs and the body prescribes the output value for every possible input combination. The example uses always statements to describe a bank of four inverters.

alyways @ (*) reevaluates statements inside the always statement anytime any of the signals on the right hand side of <= or = inside the always statement change. Thus, @ (**) is a safe way to model combinational logic. in this particular example, @ (a) would also have sufficed.

The = in the always statement is called a blocking assignment, in contrast to the <= nonblocking assignment. In Verilog, it is good practice to use blocking assignments for combinational logic and nonbloocking assignments for sequential logic.

Note that y must be declared as reg because it appears on the left hand side of a <= or = sign in an always statement. Nevertheless, y is the output of combinational logic, not a register.

module inv (input [3:0] a,

output reg [3:0] y);

always @ (*)

y = ~a;

endmodule

HDLs support blocking and nonblocking assignments in an always statement. A group of blocking assignments are evaluated in the order in which they appear in the code, just as one would expect in a standard programming language. A group of nonblocking assignments are evaluated concurrently; all of the statements are evaluated before any of the signals on the left hand sides are updated.

The example defines a full adder using intermediate signals p and g to compute s and cout. It produces the same circuit from earlier, but uses always statements in place of assignment statements.

In this case, an @ (a, b, cin) would have been equivalent to @ (*). However, @ (**) is better because it avoids common mistakes of missing signals in the stimulus list.

For reasons that will be discussed later, it is best to use blocking assignments for combinational logic. This example uses blocking assignments, first computing p, then q, then s and finally cout.

Because p and g appear on the left hand side of an assignment in an always statement, they must be declared to be reg.

module fulladder (input a, b, cin,

output reg s, cout);

reg p, g;

always @ (*)

begin

p = a ^ b; // blocking

g = a & b; // blocking

s = p ^ cin; // blocking

cout = g | (p & cin); // blocking

end

endmodule

These two examples are poor applications of always statements for modeling combinational logic because they require more lines than the equivalent approach with assignment statements from earlier. Moreover, they pose the risk of inadvertently implying sequential logic if the inputs are left out of the sensitivity list. However, case and if statements are convenient for modeling more complicated combinational logic. case and if statements must appear within always statements and are examined in the next sections.

In a Verilog always statement, = indicates a blocking assignment and <= indicates a non-blocking assignment (also called a concurrent assignment).

Do not confuse either type with continuous assignment using the assign statement. assign statements must be used outside always statements and are also evaluated concurrently.

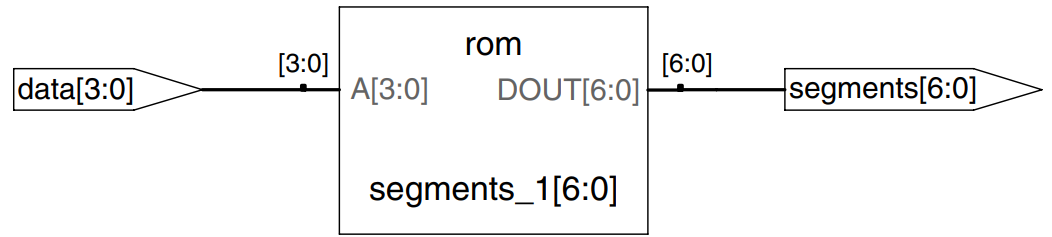

Case Statements

A better application of using the always statement for combinational logic is a seven-segment display decoder that takes advantage of the case statement that must appear inside an always statement.

As one might have noticed, the design process for large blocks of combinational logic is tedious and prone to error. HDLs offer a great improvement, allowing you to specify the function at a higher level of abstraction, and then automatically synthesize the function into gates. The example uses case statements to describe a seven-segment display decoder based on its truth table. The case statement performs different actions depending on the value of its input. A case statement implies combinational logic if all possible input combinations are defined; otherwise it implies sequential logic, because the output will keep its old value in the undefined cases. The synthesizer used synthesizes the seven-segment display decoder into a read-only memory (ROM) containing the 7 outputs for each of the 16 possible inputs. ROMs are discussed further later.

If the default clause were left out of the case statement, the decoder would have remembered its previous output anytime data were in the range of 10-15. This is strange behavior for hardware.

The case statement checks the value of data. When data is 0, the statement performs the action after the colon, setting segments to 1111110. The case statement similarly checks other data values up to 9 (note the use of the default base, base 10).

The default clause is a convenient way to define the output for all cases not explicitly listed, guaranteeing combinational logic.

In Verilog, case statements must appear inside always statements.

module sevenseg (input [3:0] data,

output reg [6:0] segments);

always @ (*)

case (data)

// abc_defg

0: segments = 7’b111_1110;

1: segments = 7’b011_0000;

2: segments = 7’b110_1101;

3: segments = 7’b111_1001;

4: segments = 7’b011_0011;

5: segments = 7’b101_1011;

6: segments = 7’b101_1111;

7: segments = 7’b111_0000;

8: segments = 7’b111_1111;

9: segments = 7’b111_1011;

default: segments = 7’b000_0000;

endcase

endmodule

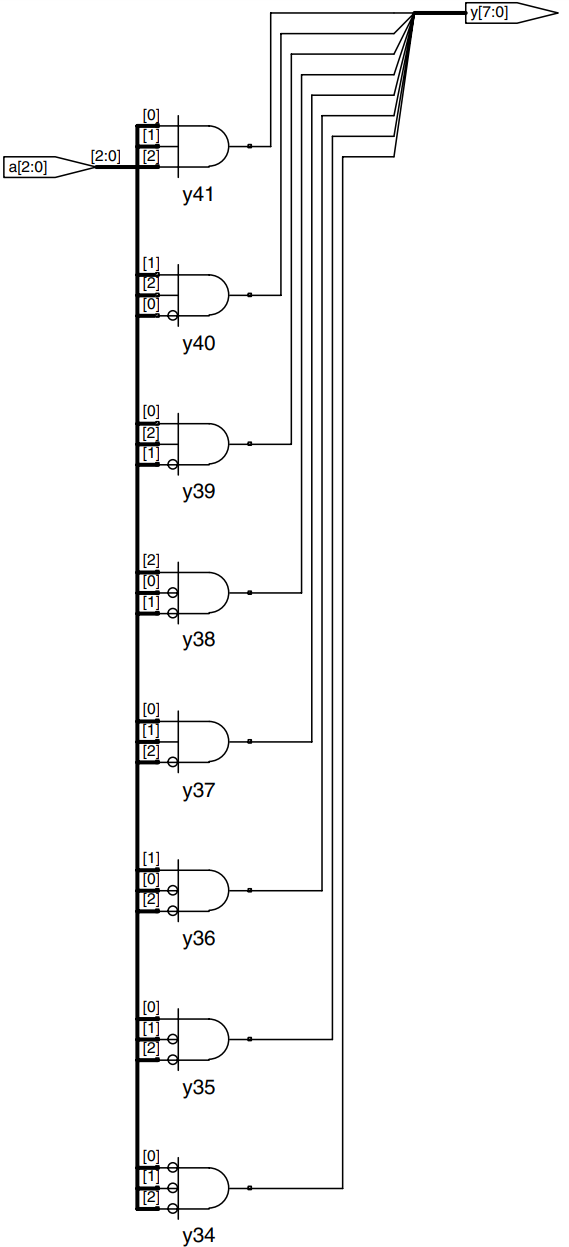

Ordinary decoders are also commonly written with case statements. The example describes a 3:8 decoder.

No default statement is needed because all cases are covered.

module decoder3_8 (input [2:0] a,

output reg [7:0] y);

always @ (*)

case (a)

3’b000: y = 8’b00000001;

3’b001: y = 8’b00000010;

3’b010: y = 8’b00000100;

3’b011: y = 8’b00001000;

3’b100: y = 8’b00010000;

3’b101: y = 8’b00100000;

3’b110: y = 8’b01000000;

3’b111: y = 8’b10000000;

endcase

endmodule

If Statements

always statements may also contain if statements. The if statement may be followed by an else statement. If all possible input combinations are handled, the statement implies combinational logic; otherwise, it produces sequential logic.

The example uses if statements to describe a priority circuit. Recall that an -input priority circuit sets the output TRUE that corresponds to the most significant input that is true.

In Verilog, if statements must appear inside of always statements.

module priority (input [3:0] a,

output reg [3:0] y);

always @ (*)

if (a[3]) y = 4’b1000;

else if (a[2]) y = 4’b0100;

else if (a[1]) y = 4’b0010;

else if (a[0]) y = 4’b0001;

else y = 4’b0000;

endmodule

Verilog casez

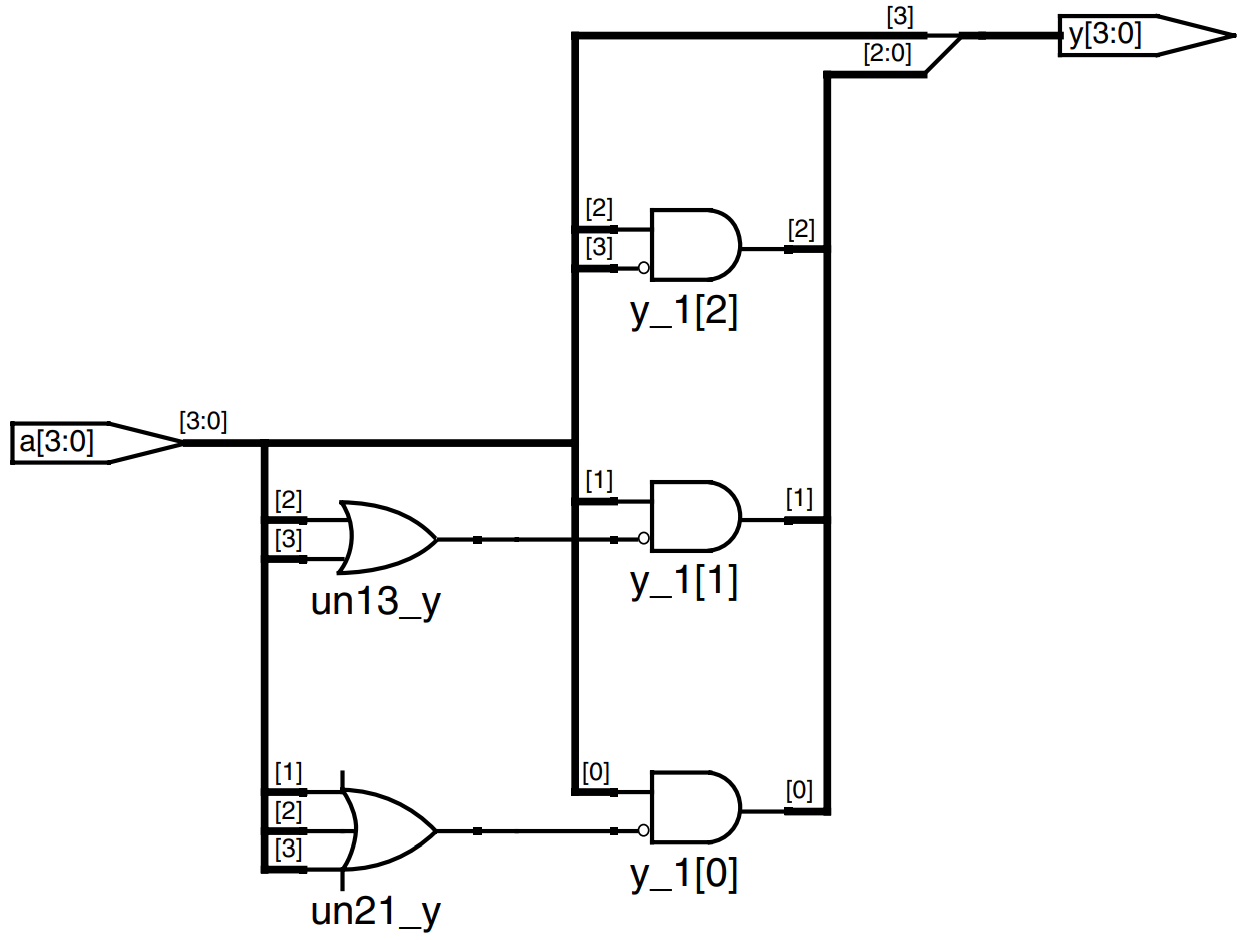

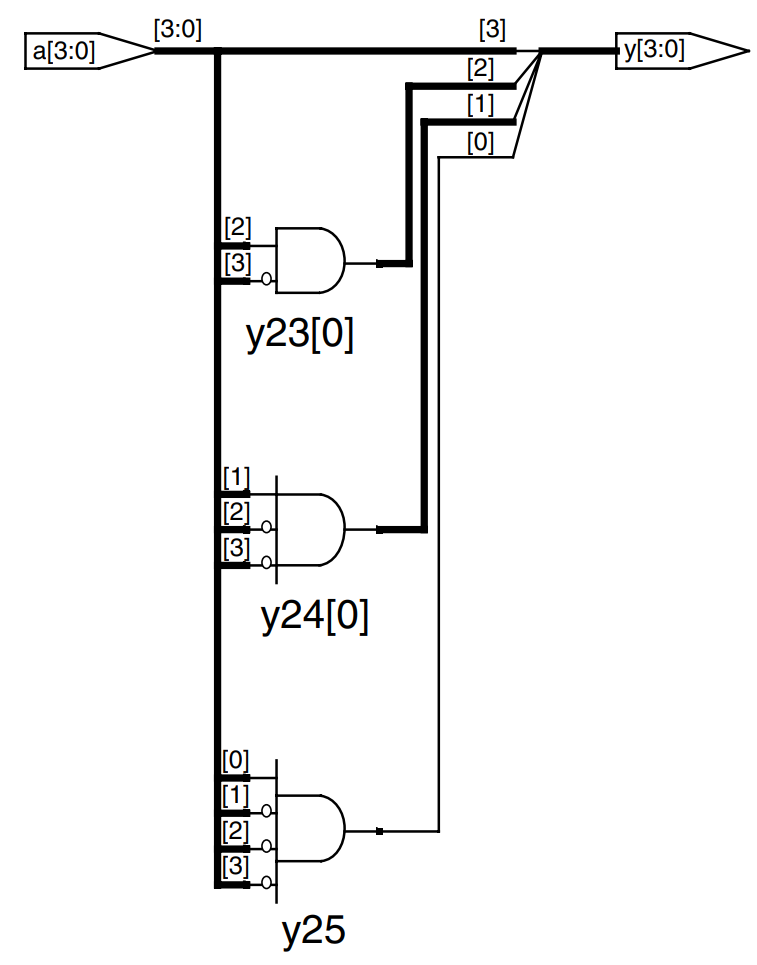

Verilog also provides the casez statement to describe truth tables with don’t cares (indicated with ? in the casez statement). The example shows how to describe a priority circuit with casez. The synthesizer used synthesizes a slightly different circuit for this module, shown in the figure, than it did for the previous priority circuit. However, the circuits are logically equivalent.

module priority_casez(input [3:0] a,

output reg [3:0] y);

always @ (*)

casez (a)

4’b1???: y = 4’b1000;

4’b01??: y = 4’b0100;

4’b001?: y = 4’b0010;

4’b0001: y = 4’b0001;

default: y = 4’b0000;

endcase

endmodule

Blocking and Nonblocking Assignments

The guidelines explaining when and how to use which type of assignment follow below. If these guidelines are not followed, it is possible to write code that appears to work in simulation but synthesizes to incorrect hardware.

-

Use

always @ (posedge clk)and nonblocking assignments to model synchronous sequential logic.always @ (posedge clk) begin nl <= d; // nonblocking q <= nl; // nonblocking end -

Use continuous assignments to model simple combinational logic.

assign y = s ? d1 : d0; -

Use

always @ (*)and blocking assignments to model more complicated combinational logic where thealwaysstatement is helpful.always @ (*) begin p = a ^ b; // blocking g = a & b; // blocking s = p ^ cin; cout = g | (p & cin); end -

Do not make assignments to the same signal in more than one

alwaysstatement or continuous assignment statement.

Combinational Logic

The full adder from above is correctly modeled using blocking assignments.

Imagine that a, b, and cin are all initially 0. p, g, s and cout are thus 0 as well. At some time, a changes to 1, triggering the always statement. The four blocking assignments evaluate in the order shown here. Note that p and g get their new values before s and cout are computed because of the blocking assignments. This is important because we want to compute s and cout using the new values of p and g.

p←g←s←cout←

In contrast, the example illustrates the use of nonblocking assignments.

Because p and g appear on the left hand side of an assignment in an always statement, they must be declared to be reg.

Now consider the same case of a rising from 0 to 1 while b and cin are 0. The four nonblocking assignments evaluate concurrently:

p ← , g ← , s ← , cout ←

Observe that s is computed concurrently with p and hence uses the old value of p, not the new value. Therefore, s remains 0 rather than becoming 1. However, p does change from 0 to 1. This change triggers the always statement to evaluate a second time, as follows:

p ← , g ← , s ← , cout ←

This time, p is already 1, so s correctly changes to 1. The nonblocking assignments eventually reach the right answer, but the always statement had to evaluate twice. This makes simulation slower, though it synthesizes to the same hardware.

If the sensitivity list of the always statement in the example were written as always @ (a, b, cin) rather than always @ (*), then the statement would not reevaluate when p or g changes. In the example, s would be incorrectly left at 0, not 1.

Another drawback of nonblocking assignments in modeling combinational logic is that the HDL will produce the wrong result if you forget to include the intermediate variables in the sensitivity list.

Worse yet, some synthesis tools will synthesize the correct hardware even when a faulty sensitivity list causes incorrect simulation. This leads to a mismatch between the simulation results and what the hardware actually does.

// nonblocking assignments (not recommended)

module fulladder (input a, b, cin,

output reg s, cout);

reg p, g;

always @ (*)

begin

p <= a ^ b; // nonblocking

g <= a & b; // nonblocking

s <= p ^ cin;

cout <= g | (p & cin);

end

endmodule

Sequential Logic

The synchronizer from the example earlier is correctly modeled using nonblocking assignments. On the rising edge of the clock, d is copied to n1 at the same time that n1 is copied to q, to the code properly describes two registers. For example, suppose initially that d = 0, n1 = 1, and q = 0. On the rising edge of the clock, the following two assignments occur concurrently, so that after the clock edge, n1 = 0 and q = 1.

n1 ← d = 0, q ← n1 = 1

The example tries to describe the same module using blocking assignments. On the rising edge of clk, d is copied to n1. Then this new value of n1 is copied to q, resulting in d improperly appearing at both n1 and q. The assignments occur one after the other so that after the clock edge, q = n1 = 0.

n1←d= 0q←n1= 0

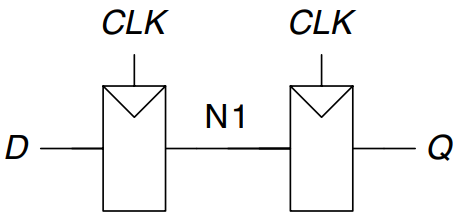

Because n1 is invisible to the outside world and does not influence the behavior of q, the synthesizer optimizes it away entirely, as shown in the figure.

The moral of this illustration is to exclusively use nonblocking assignment in always statements when modeling sequential logic. With sufficient cleverness, such as reversing the orders of the assignments, you could make blocking assignments work correctly, but blocking assignments offer no advantages and only introduce the risk of unintended behavior. Certain sequential circuits will not work with blocking assignments no matter what the order.

// Bad implementation using blocking assignments

module syncbad (input clk,

input d,

output reg q);

reg n1;

always @ (posedge clk)

begin

n1 = d; // blocking

q = n1; // blocking

end

endmodule

Finite State Machines

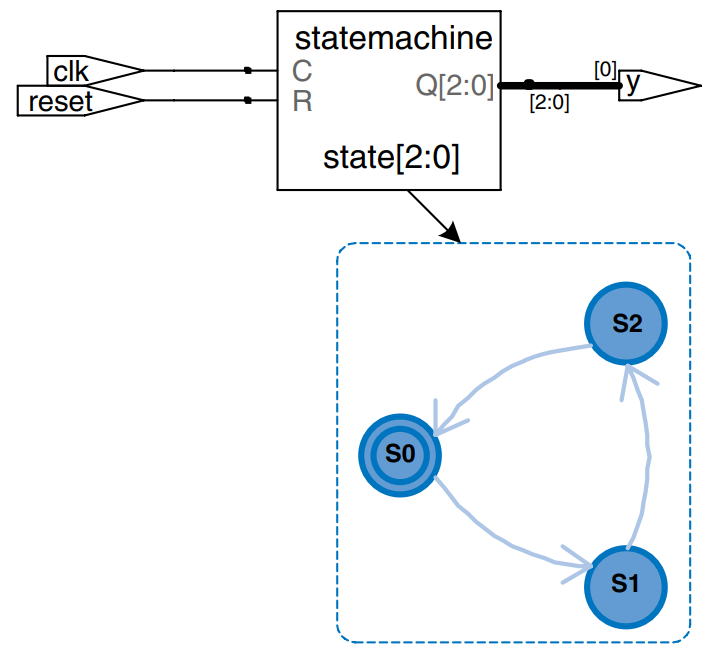

Recall that a finite state machine consists of a state register and two blocks of combinational logic to compute the next state and the output given the current state and the input. HDL descriptions of state machines are correspondingly divided into three parts to model the state register, the next state logic, and the output logic.

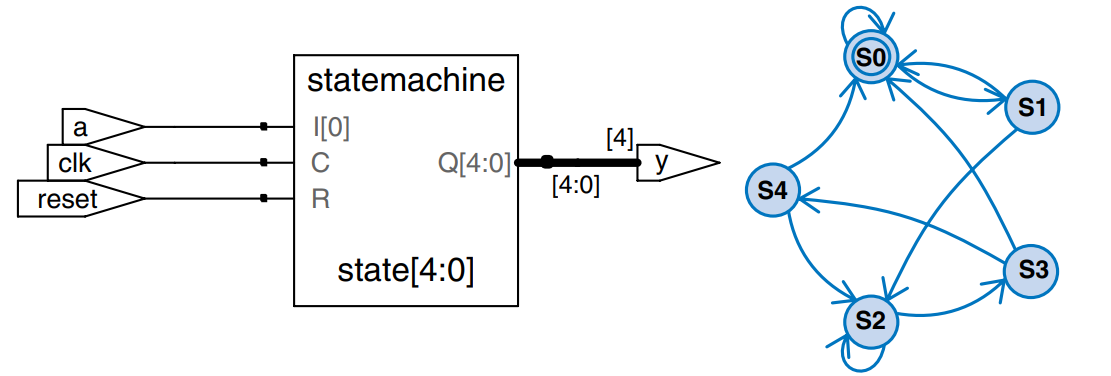

The example describes the divide-by-3 FSM from earlier. It provides an asynchronous reset to initialize the FSM. The state register uses the ordinary idiom for flip-flops. The next state and output logic blocks are combinational.

The parameter statement is used to define constants within a module. Naming the states with parameters is not required, but it makes changing state encodings much easier and makes the code more readable.

Notice how a case statement is used to define the state transition table. Because the next state logic should be combinational, a default is necessary even though the state 2'b11 should never arise.

The output, y, is 1 when the state is S0. The equality comparison a == b evaluates to 1 if a equals b and 0 otherwise. The inequality comparison a != b does the inverse, evaluating to 1 if a does not equal b.

The synthesis tool used just produces a block diagram and state transition diagram for state machines; it does not show the logic gates or the inputs and outputs on the arcs and states. Therefore, be careful that you have specified the FSM correctly in your HDL code. The state transition diagram for the divide-by-3 FSM is analogous to the diagram we saw earlier. The double circle indicates that S0 is the reset state.

If for some reason, we had wanted the output to be HIGH in states S= and S1, the output logic would be modified as follows:

// output logic

assign y = (state == S0 | state == S1);

module divideby3FSM (input clk,

input reset,

output y);

reg [1:0] state, nextstate;

parameter S0 2b00;

parameter S1 2b01;

parameter S2 2b10;

// state register

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) state <= S0;

else state <= nextstate;

// next state logic

always @ (*)

case (state)

S0: nextstate = S1;

S1: nextstate = S2;

S2: nextstate = S0;

default: nextstate = S0;

endcase

// output logic

assign y = (state == S0);

endmodule

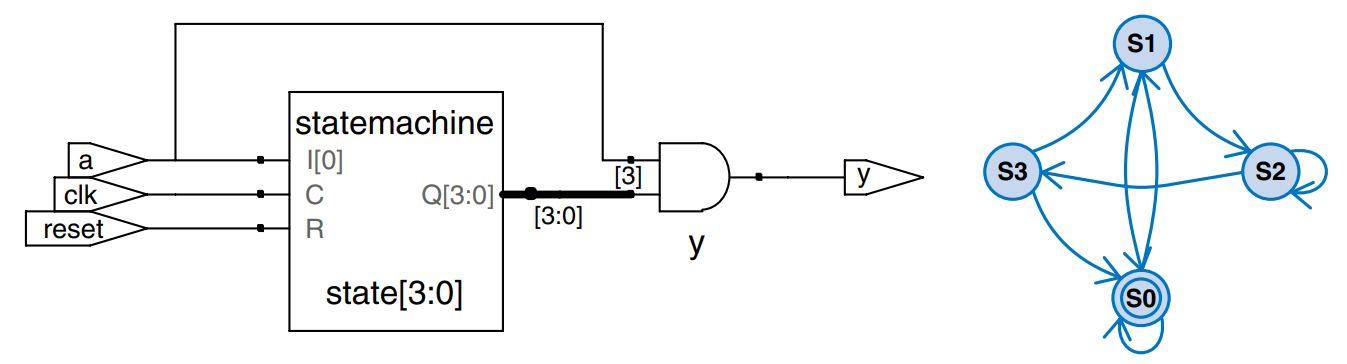

The next two examples describe the snail pattern recognizer FSM from earlier. The code shows how to use case and if statements to handle next state and output logic that depend on the inputs as well as the current state. We show both Moore and Mealy modules. In the Moore machine, the output depends only on the current state, whereas in the Mealy machine, the output logic depends on both the current state and inputs.

Moore FSM

Note how nonblocking assignments (<=) are used in the register to describe sequential logic, whereas blocking assignments (=) are used in the next state logic to describe combinational logic.

module patternMoore (input clk,

input reset,

input a,

output y);

reg [2:0] state, nextstate;

parameter S0 = 3b000;

parameter S1 = 3b001;

parameter S2 = 3b010;

parameter S3 = 3b011;

parameter S4 = 3b100;

// state register

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) state <= S0;

else state <= nextstate;

// next state logic

always @ (*)

case (state)

S0: if (a) nextstate = S1;

else nextstate = S0;

S1: if (a) nextstate = S2;

else nextstate = S0;

S2: if (a) nextstate = S2;

else nextstate = S3;

S3: if (a) nextstate = S4;

else nextstate = S0;

S4: if (a) nextstate = S2;

else nextstate = S0;

default: nextstate = S0;

endcase

// output logic

assign y = (state == S4);

endmodule

Mealy FSM

module patternMealy (input clk,

input reset,

input a,

output y);

reg [1:0] state, nextstate;

parameter S0 = 2b00;

parameter S1 = 2b01;

parameter S2 = 2b10;

parameter S3 = 2b11;

// state register

always @ (posedge clk, posedge reset)

if (reset) state <= S0;

else state <= nextstate;

// next state logic

always @ (*)

case (state)

S0: if (a) nextstate = S1;

else nextstate = S0;

S1: if (a) nextstate = S2;

else nextstate = S0;

S2: if (a) nextstate = S2;

else nextstate = S3;

S3: if (a) nextstate = S1;

else nextstate = S0;

default: nextstate = S0;

endcase

// output logic

assign y = (a & state == S3);

endmodule

Parameterized Modules

So far all of our modules have had fixed-width inputs and outputs. For example, we had to define separate modules for 4- and 8-bit wide 2:1 multiplexers. HDLs permit variable bit widths using parameterized modules.

Parameterized -bit Multiplexers

Verilog allows a # (parameter ... ) statement before the inputs and outputs to define parameters. The parameter statement includes a default value (8) of the parameter, width. The number of bits in the inputs and outputs can depend on this parameter.

module mux2

# (parameter width = 8)

(input [width-1:0] d0, d1,

input s,

output [width-1:0] y);

assign y s ? d1 : d0;

endmodule

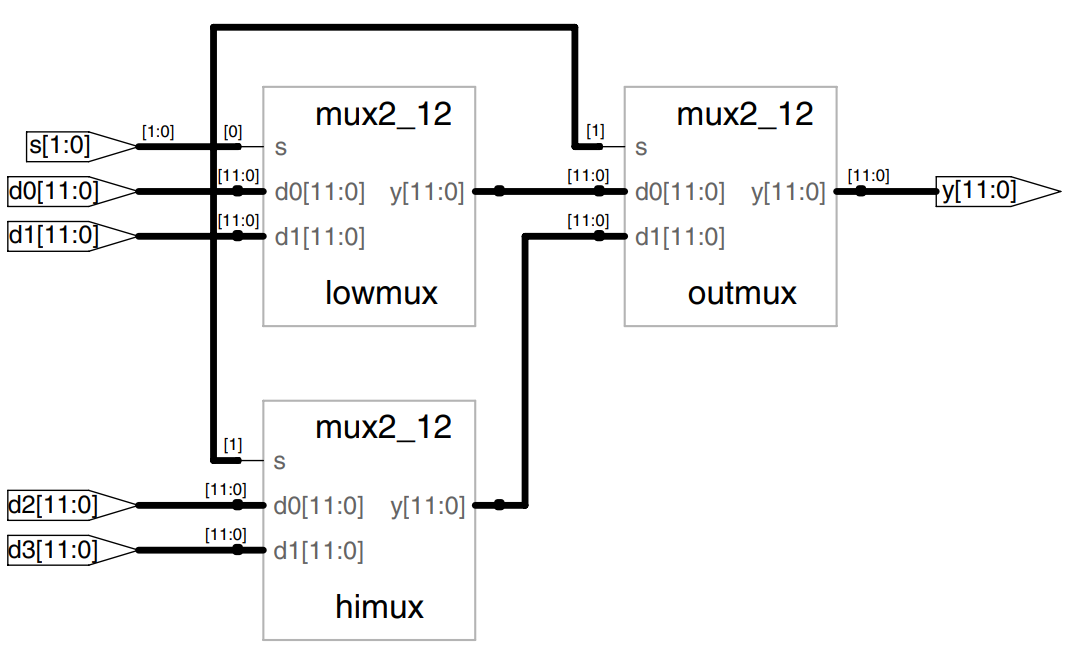

The 8-bit 4:1 multiplexer instantiates three 2:1 multiplexers using their default widths.

module mux4_8 (input [7:0] d0, d1, d2, d3,

input [1:0] s,

output [7:0] y);

wire [7:0] low, hi;

mux2 lowmux (d0, d1, s[0], low);

mux2 himux (d2, d3, s[1], hi);

mux2 outmux (low, hi, s[1], y);

endmodule

In contrast, a 12-bit 4:1 multiplexer, mux4_12, would need to override the default width using #() before the instance name, as shown below.

Do not confuse the use of the # sign indicating delays with the use of #(...) in defining and overriding parameters.

This example declares a parameterized 2:1 multiplexer with a default width of 8, then uses it to create 8- and 12-bit 4:1 multiplexers.

module mux4_12 (input [11:0] d0, d1, d2, d3,

input [1:0] s,

output [11:0] y);

wire [11:0] low, hi;

mux2 #(12) lowmux(d0, d1, s[0], low);

mux2 #(12) himux(d2, d3, s[1], hi);

mux2 #(12) outmux(low, hi, s[1], y);

endmodule

Parameterized : Decoder

2**N indicates .

This example shows a decoder, which is an even better application of parameterized modules. A large : decoder is cumbersome to specify with case statements, but easy using parameterized code that simply sets the appropriate output bit to 1. Specifically, the decoder uses blocking assignments to set all the bits to 0, then changes the appropriate bit to 1.

module decoder # (parameter N = 3)

(input [N-1:0] a,

output reg [2**N-1:0] y);

always @ (*)

begin

y = 0;

y[a] = 1;

end

endmodule

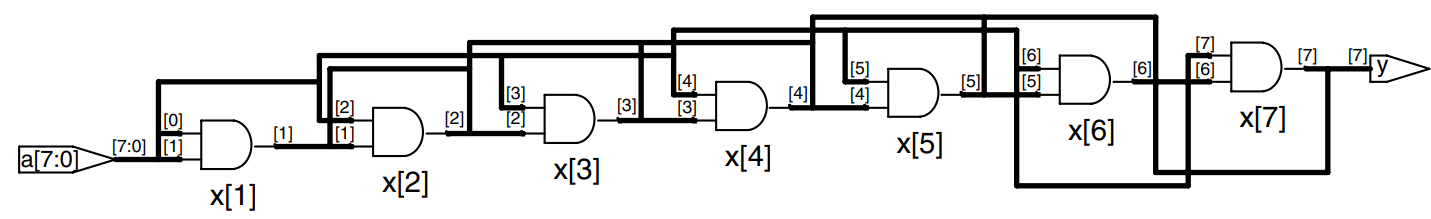

Parameterized -Input Gate

HDLs also provide generate statements to produce a variable amount of hardware depending on the value of a parameter. generate supports for loops and if statements to determine how many of what types of hardware to produce.

The example uses generate statements to produce an -input function from a cascade of two-input gates.

Use generate statements with caution; it is easy to produce a large amount of hardware unintentionally.

The for statement loops through i = 1, 2, ..., width - 1 to produce many consecutive gates. The begin in a generate for loop mmust be followed by a : and an arbitrary label (forloop, in this case).

Of course, writing assign y = &a would be much easier.

module andN

# (parameter width = 8)

(input [width-1:0] a,

output y);

genvar i;

wire [width-1:1] x;

generate

for (i=1; i<width; i=i+1) begin:forloop

if (i == 1)

assign x[1] = a[0] & a[1];

else

assign x[i] = a[i] & x[i-1];

end

endgenerate

assign y = x[width-1];

endmodule

Testbenches

A testbench is an HDL module that is used to test another module, called the device under test (DUT). The testbench contains statements to apply inputs to the DUT and, ideally, to check that the correct outputs are produced. The input and desired output patterns are called test vectors.

Consider testing the sillyfunction module from the first example of this page that computes

. This is a simple module, so we can perform exhaustive testing by applying all eight possible test vectors.

The example demonstrates a simple testbench. It instantiates the DUT, then applies the inputs. Blocking assignments and delays are used to apply the inputs in the appropriate order. The user must view the results of the simulation and verify by inspection that the correct outputs are produced. Testbenches are simulates as every other HDL module. However, they are not synthesizable.

The initial statement executes the statements in its body at the start of simulation. In this case, it first applies the input pattern 000 and waits for 10 time units. It then applies 001 and waits 10 more units, and so forth until all eight possible inputs have been applied. initial statements should be used only in testbenches for simulation, not in modules intended to be synthesized into actual hardware. Hardware has no way of magically executing a sequence of special steps when it is first turned on.

Like signals in always statements, signals in initial statements must be declared to be reg.

module testbench1 ();

reg a, b, c;

wire y;

// instantiate device under test

sillyfunction dut (a, b, c, y);

// apply inputs one at a time

initial begin

a = 0; b = 0; c = 0; #10;

c = 1; #10;

b = 1; c = 0; #10;

c = 1; #10;

a = 1; b = 0; c = 0; #10;

c = 1; #10;

b = 1; c = 0; #10;

c = 1; #10;

end

endmodule

Checking for correct outputs is tedious and error-prone. Moreover, determining the correct outputs is much easier when the design is fresh in your mind; if you make minor changes and need to retest weeks later, determining the correct outputs becomes a hassle. A much better approach is to write a self-checking testbench, as shown in the example.

This module checks y against expectations after each input test vector is applied. In Verilog, comparison using == or != is effective between signals that do not take on the values of x and z. Testbenches use the === and !== operators for comparisons of equality and inequality, respectively, because these operators work correctly with operands that could be x or z. It uses the $display system task to print a message on the simulator console if an error occurs. $display is meaningful only in simulation, not synthesis.

module testbench2 ();

reg a, b, c;

wire y;

// instantiate device under test

sillyfunction dut (a, b, c, y);

// apply inputs one at a time

// checking results

initial begin

a = 0; b = 0; c = 0; #10;

if (y !== 1) $display(“000 failed.”);

c = 1; #10;

if (y !== 0) $display(“001 failed.”);

b = 1; c = 0; #10;

if (y !== 0) $display(“010 failed.”);

c = 1; #10;

if (y !== 0) $display(“011 failed.”);

a = 1; b = 0; c = 0; #10;

if (y !== 1) $display(“100 failed.”);

c = 1; #10;

if (y !== 1) $display(“101 failed.”);

b = 1; c = 0; #10;

if (y !== 0) $display(“110 failed.”);

c = 1; #10;

if (y !== 0) $display(“111 failed.”);

end

endmodule

Writing code for each test vector also becomes tedious, especially for modules that require a large number of vectors. An even better approach is to place the test vectors in a separate file. The testbench simply reads the test vectors from the file, applies the input test vector to the DUT, waits, checks that the output values from the DUT match the output vector, and repeats until reaching the end of the test vectors file. The example demonstrates such a testbench. The testbench generates a clock using an always statement with no stimulus list, so that it is continuously reevaluated. At the beginning of the simulation, it reads the test vectors from a text file and pulses reset for two cycles. [example.tv](http://example.tv) is a text file containing the inputs and expected output written in binary:

000_1

001_0

010_0

011_0

100_1

101_1

110_0

111_0

$readmmemb reads a file of binary numbers into the testvectors array. $readmemh is similar but reads a file of hexadecimal numbers.

The next block of code waits one time unit after the rising edge of the clock (to avoid any confusion if clock and data change simultaneously), then sets the three inputs and the expected output based on the four bits in the current test vector. The next block of code checks the output of the DUT at the negative edge of the clock, after the inputs have had time to propagate through the DUT to produce the output, y. The testbench compares the generated output, y, with the expected output, yexpected, and prints an error if they don’t match. %b and %d indicate to print the values in binary and decimal, respectively. %h prints a value in hexadecimal.

This process repeats until there are no more valid test vectors in the testvectors array. $finish terminates the simulation.

Not that even though the Verilog module supports up to 10’001 test vectors, it will terminate the simulation after executing the eight vectors in the file.

New inputs are applied on the rising edge of the clock, and the output is checked on the falling edge of the clock. This clock (and reset) would also be provided to the DUT if sequential logic were being tested. Errors are reported as they occur. At the end of the simulation, the testbench prints the total number of test vectors applied and the number of errors detected.

The testbench in this example is overkill for such a simple circuit. However, it can easily be modified to test more complex circuits by changing the [example.tv](http://example.tv) file, instantiating the new DUT, and changing a few lines of code to set the inputs and check the outputs.

module testbench3 ();

reg clk, reset;

reg a, b, c, yexpected;

wire y;

reg [31:0] vectornum, errors;

reg [3:0] testvectors [10000:0];

// instantiate device under test

sillyfunction dut (a, b, c, y);

// generate clock

always

begin

clk = 1; #5; clk = 0; #5;

end

// at start of test, load vectors

// and pulse reset

initial

begin

$readmemb (“example.tv”, testvectors);

vectornum = 0; errors = 0;

reset = 1; #27; reset = 0;

end

// apply test vectors on rising edge of clk

always @ (posedge clk)

begin

#1; {a, b, c, yexpected} =

testvectors[vectornum];

end

// check results on falling edge of clk

always @ (negedge clk)

if (~reset) begin // skip during reset

if (y !== yexpected) begin

$display (“Error: inputs = %b”, {a, b, c});

$display (“ outputs = %b (%b expected)”,

y, yexpected);

errors = errors + 1;

end

vectornum = vectornum + 1;

if (testvectors[vectornum] === 4’bx) begin

$display (“%d tests completed with %d errors”,

vectornum, errors);

$finish;

end

end

endmodule